✨ Introduction

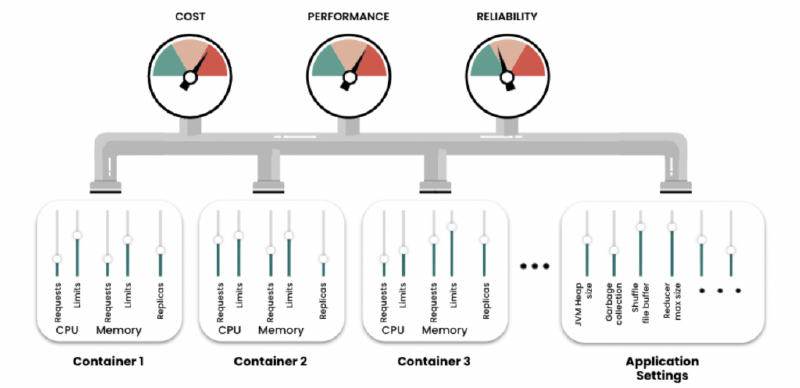

Managing resource requests and limits in Kubernetes is a constant balancing act between performance, stability, and cloud bills. Recently, I tackled an optimization challenge for one of our critical, event-driven microservices.

This services are powered by KEDA (Kubernetes Event-driven Autoscaling). It sits idle at 0 replicas until awoken by one of two specific event triggers (handling the 0 $\rightarrow$ 1 scale). Once running, standard CPU-based HPA takes over, scaling between 1 and a maximum of 10 replicas.

The Problem: The services felt sluggish under load. They would aggressively scale straight to their maximum of 10 replicas in almost every environment, yet throughput wasn’t improving as expected. Our goal was to stabilize performance in Production while keeping costs down in our numerous Development environments.

🔍 Phase 1: The Load Testing Revelation

I conducted rigorous load tests against the microservices. I kept memory settings constant (800Mi limit, which sat comfortably around 69% utilization during tests) and high CPU limits (1500m) for startup bursting. The variable I changed was the CPU Request.

The results were counter-intuitive at first glance:

Test Scenario A: The “Cheaper” Config 📉

- CPU Request:

100m - Result: The services struggled. They panicked and quickly scaled to the maximum of 10 pods. Despite maxing out replicas, response times were slow.

Test Scenario B: The “Expensive” Config 📈

- CPU Request:

200m(Doubled the guaranteed CPU) - Result: The services performed significantly faster. Surprisingly, they only needed to scale to 8 pods to handle the same load comfortably.

The “Aha!” Moment 💡

Why was the configuration with fewer pods faster?

When the CPU request was too low (100m), the pods had a weak guarantee from the Kubernetes scheduler. Under load on busy nodes, they were likely being throttled. The HPA saw high individual utilization relative to the tiny request and scaled out to the max. We had 10 weak, struggling pods.

By doubling the request to 200m, we gave each pod a stronger guarantee of CPU time. They stopped throttling and processed chunks efficiently. Because individual pods were more powerful, the total replica count needed to settle actually dropped.

🎯 Phase 2: The Environment Strategy

Based on the testing data, we defined a clear resource strategy:

PROD Profile (Focus: Stability & Speed) 🛡️ - Use higher CPU requests (200m) to guarantee performance and prevent thrashing. - Keep high limits (1500m) for ultra-fast Java JVM startup when KEDA wakes them from zero.

DEV Profile (Focus: Cost Efficiency) 💰 - Use lower CPU requests (100m) to increase pod density on nodes and save money across our many dev clusters. - Accept slightly slower peak performance as a trade-off.

⚙️ Phase 3: The Helm Implementation Challenge

Implementing this strategy revealed a flaw in our existing Helm deployment architecture.

We use a standard GitOps approach where a shared prod/values.yaml file overrides settings for every microservice deployed to production.

If we defined requests.cpu: 200m in that shared PROD file, it would apply to every single service in our ecosystem. I had no easy way to specify that only the specified variant needed 200m in PROD, while another service might only need 50m. Standard Helm merging had hit a wall.

🛠️ Phase 4: The Template “Mapper” Solution

Instead of complicating our deployment scripts with dozens of specific override files, I decided to make the Helm deployment.yaml template smarter. We turned it into a “mapper.”

We restructured our values files to define all environment variations directly within the service’s own configuration file, and updated the template to dynamically select the right one.

The New Service Values Structure 🗂️

In the service-specific file (values/microservice_variant.yaml), we now define resources under generic keys like dev and prod:

| |

The Environment Identifier 🏷️

In every environment-specific values file (e.g., values/dev/dev-1/values.yaml or values/prod/values.yaml), we added a simple identifier variable to tell Helm where it is running:

| |

The Smart Helm Template Logic 🧠

Finally, we updated the shared templates/deployment.yaml. It now takes the specific environment name (like dev-1 or dev-rc), maps it to a generic key (like dev), and looks up the correct resource block.

| |

🚀 Conclusion

By combining targeted performance testing with some clever Helm templating, we moved from a struggling, “one-size-fits-all” configuration to a flexible, environment-aware setup.

The microservices now have the robust resources they need to wake up instantly via KEDA and perform stably in Production, while maintaining a leaner footprint in development, all managed cleanly within our existing GitOps structure.